A recently revealed mobile malware campaign targeting Uyghur Muslims also ensnared a number of senior Tibetan officials and activists, according to new research.

Security researchers at the University of Toronto’s Citizen Lab say some of the Tibetan targets were sent specifically tailored malicious web links over WhatsApp, which, when opened, could have stealthily gained full access to their phone, installed spyware and silently stole private and sensitive information.

The exploits shared “technical overlaps” with a recently disclosed campaign targeting Uyghur Muslims, an oppressed minority in China’s Xinjiang state. Google last month disclosed the details of the campaign, which targeted iPhone users, but did not say who was targeted or who was behind the attack. Sources told TechCrunch that Beijing was to blame. Apple, which patched the vulnerabilities, later confirmed the exploits targeted Uyghurs.

Although Citizen Lab would not specify who was behind the latest round of attacks, the researchers said the same group targeting both Uyghurs and Tibetans also utilized Android exploits. Those exploits, recently disclosed and detailed by security firm Volexity, were used to steal text messages, contact lists and call logs, as well as watch and listen through the device’s camera and microphone.

It’s the latest move in a marked escalation of attacks on ethnic minority groups under surveillance and subjection by Beijing. China has long claimed rights to Tibet, but many Tibetans hold allegiance to the country’s spiritual leader, the Dalai Lama. Rights groups say China continues to oppress the Tibetan people, just as it does with Uyghurs.

A spokesperson for the Chinese consulate in New York did not return an email requesting comment, but China has long denied state-backed hacking efforts, despite a consistent stream of evidence to the contrary. Although China has recognized it has taken action against Uyghurs on the mainland, it instead categorizes its mass forced detentions of more than a million Chinese citizens as “re-education” efforts, a claim widely refuted by the west.

The hacking group, which Citizen Lab calls “Poison Carp,” uses the same exploits, spyware and infrastructure to target Tibetans as well as Uyghurs, including officials in the Dalai Lama’s office, parliamentarians and human rights groups.

Bill Marczak, a research fellow at Citizen Lab, said the campaign was a “major escalation” in efforts to access and sabotage these Tibetans groups.

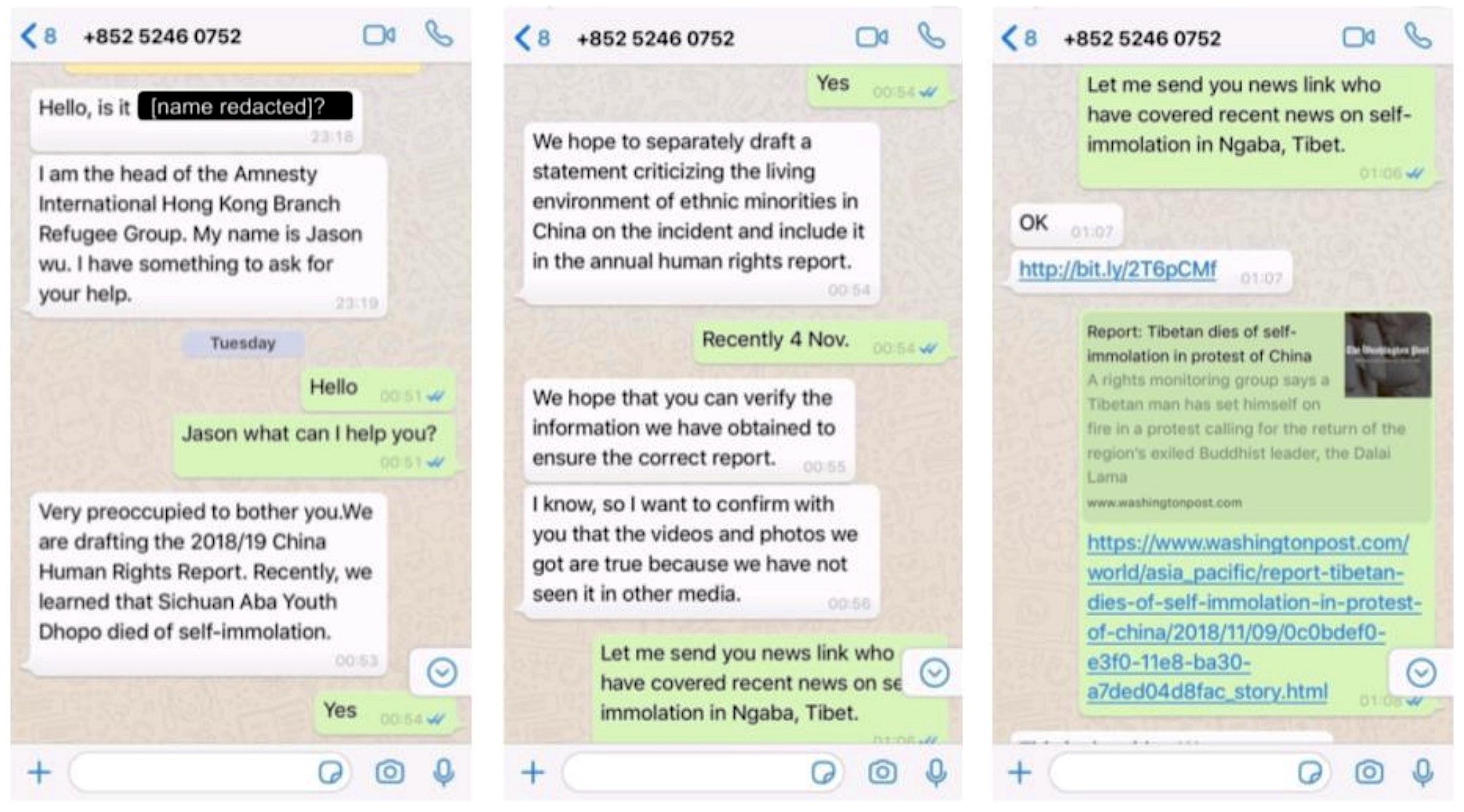

In its new research out Tuesday and shared with TechCrunch, Citizen Lab said a number of Tibetan victims were targeted with malicious links sent in WhatsApp messages by individuals purporting to work for Amnesty International and The New York Times. The researchers obtained some of those WhatsApp messages from TibCERT, a Tibetan coalition for sharing threat intelligence, and found each message was designed to trick each target into clicking the link containing the exploit. The links were disguised using a link-shortening service, allowing the attackers to mask the full web address but also gain insight into how many people clicked on a link and when.

“The ruse was persuasive,” the researchers wrote. During a week-long period in November 2018, the targeted victims opened more than half of the attempted infections. Not all were infected, however; all of the targets were running non-vulnerable iPhone software.

One of the specific social engineering messages, pretending to be an Amnesty International aid worker, targeting Tibetan officials (Image: Citizen Lab/supplied)

The researchers said tapping on a malicious link targeting iPhones would trigger a chain of exploits designed to target a number of vulnerabilities, one after the other, in order to gain access to the underlying, typically off-limits, iPhone software.

The chain “ultimately executed a spyware payload designed to steal data from a range of applications and services,” said the report.

Once the exploitation had been achieved, a spyware implant would be installed, allowing the attackers to collect and send data to the attackers’ command and control server, including locations, contacts, call history, text messages and more. The implant also would exfiltrate data, like messages and content, from a hardcoded list of apps — most of which are popular with Asian users, like QQMail and Viber.

Apple had fixed the vulnerabilities months earlier (in July 2018); they were later confirmed as the same flaws found by Google earlier this month.

“Our customers’ data security is one of Apple’s highest priorities and we greatly value our collaboration with security researchers like Citizen Lab,” an Apple spokesperson told TechCrunch. “The iOS issue detailed in the report had already been discovered and patched by the security team at Apple. We always encourage customers to download the latest version of iOS for the best and most current security enhancements.”

Meanwhile, the researchers found that the Android-based attacks would detect which version of Chrome was running on the device and would serve a matching exploit. Those exploits had been disclosed and were “obviously copied” from previously released proof-of-concept code published by their finders on bug trackers, said Marczak. A successful exploitation would trick the device into opening Facebook’s in-app Chrome browser, which gives the spyware implant access to device data by taking advantage of Facebook’s vast number of device permissions.

The researchers said the code suggests the implant could be installed in a similar way using Facebook Messenger, and messaging apps WeChat and QQ, but failed to work in the researchers’ testing.

Once installed, the implant downloads plugins from the attacker’s server in order to collect contacts, messages, locations and access to the device’s camera and microphone.

A Google spokesperson said: “”We collaborated with Citizen Lab on this research and appreciate their efforts to improve security across all platforms. As noted in the report, these issues were patched, and no longer pose a risk to users’ with up-to-date software.”

Facebook, which received Citizen Lab’s report on the exploit activity in November 2018, did not comment at the time of publication.

“From an adversary perspective what makes mobile an attractive spying target is obvious,” the researchers wrote. “It’s on mobile devices that we consolidate our online lives and for civil society that also means organizing and mobilizing social movements that a government may view as threatening.”

“A view inside a phone can give a view inside these movements,” they said.

The researchers also found another wave of links trying to trick a Tibetan parliamentarian into allowing a malicious app access to their Gmail account.

Citizen Lab said the threat from the mobile malware campaign was a “game changer.”

“These campaigns are the first documented cases of iOS exploits and spyware being used against these communities,” the researchers wrote. But attacks like Poison Carp show mobile threats “are not expected by the community,” as shown by the high click rates on the exploit links.

Gyatso Sither, TibCERT’s secretary, said the highly targeted nature of these attacks presents a “huge challenge” for the security of Tibetans.

“The only way to mitigate these threats is through collaborative sharing and awareness,” he said.

Updated with Google comment.

Read More

Comments

Post a Comment